What’s not to love about those “petrol-powered centaurs”?

Nick Foulkes takes a ride in the Southern Alps

As much a part of the Italian cityscape as overpriced ice cream and historic architecture, the Vespa is one of the great visual (and aural) signs that you have arrived in Italy. Gathering in swarms like their namesake insect, these petrol-powered centaurs bring a new dimension to motoring south of the Alps. A few years ago I was on assignment for the Sunday Times, driving a Bentley down from Portofino to the Amalfi Coast. It is the kind of fearless reporting that I go in for and I needed to screw my courage to the sticking-place when confronting one of the great features of Italy’s minor roads: the Piaggio Ape.

‘The Ape is a Vespa over which someone has placed a large bread tin with a windscreen and door’

In English it sounds simian, and it is the sort of thing that a monkey could indeed operate – from the way they are driven it appears that not a few are – but the name translates as bee, and as such they are the counterpart to the swarms of Vespas that gather in Italian cities. The Ape is a Vespa over which someone has placed a large bread tin with a windscreen and door, then attached a trailer. What they lack in rapidity (I cannot recall one topping 53kph) their drivers compensate for with a fatalistic and flamboyant abandon.

I have to admit that over four or five days I gained a sneaking admiration for these ingenious vehicles, which were turned into everything from mobile fruit stalls to mini-meat wagons. And as well as serving as delivery wagons, during the 1950s it was available as a low cost family vehicle (named the Calessino). With a fold back pram-like hood and wood-bodied passenger compartment, it was the Italian version of motor-scooter-as-rickshaw. The Calessino was recently revived in a limited edition, but that was after my Italian road trip, so I was deprived of the sight of large Italian families tearing up and down mountain roads and careering around country lanes, packed precariously into a motor-scooter that thinks it is a golf cart.

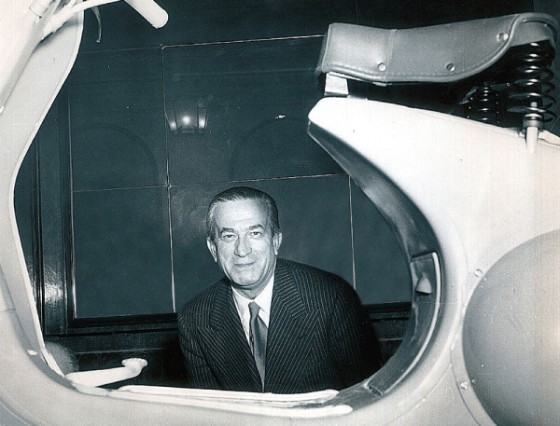

Enrico Piaggio, the man behind the Vespa

I enjoyed this road-going link to Italy’s post war history. By the time hostilities came to an end, the shocking state of the roads eclipsed only by the dire economic straits the country found itself in. The country needed to get on the move and soon the Vespa started buzzing around a liberated Italy as the citizens of the war-ravaged country sought low cost, easily operated motor transport. Of course it was not long before the scooter became a style statement: it takes a nation like Italy to turn an economic necessity into a fashion accessory. In post-war England we had Spam and prefab housing made of asbestos; in Italy they had espresso coffee and the Vespa.

Not only did the Vespa get the nation moving, it also came to the rescue of Piaggio. A leading aircraft builder during the Second World War, it was heavily bombed and for under the terms of the peace, the Italian manufacture of military aircraft was prohibited for a decade.

Understandably, Enrico Piaggio, son of the founder Rinaldo, seized the opportunity to make anything, even if it was a scooter. Along with engineer Corradino d’Ascanio, he created the totemic two wheeler that was to co-star along with Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday. D’Ascanio, who would later develop the first helicopter for Agusta, had enjoyed a distinguished career as an innovative aeronautical engineer and his work was regarded as so crucial to the Italian war effort that he was given the rank of general in the Italian air force. However, this was not a credential that he could flash about in the post war labour market and in his mid fifties, as talented as ever and at the peak of his powers, he found himself unemployed. Designing something as humble as a motor scooter must have seemed a humiliating comedown.

For his part, it is said that d’Ascanio remained frustrated that he was better remembered for making a motor scooter than for his advanced aeronautical work. The reason for that of course is that while it takes a particular kind of mind to appreciate the value of high speed adjustable pitch propellers, the idea of a motor scooter is slightly easier to grasp for the greater run of humanity, particularly when it is as distinctive as the Vespa. The feature that would become the Vespa’s design signature and ensure its popularity was its step-through construction, which had been a feature of among others, a scooter design used by the American forces when they invaded Italy. D’Ascanio was able to eliminate the centre section by getting rid of the drive chain, and it is probably the resulting ultra-thin ‘wasp waist’ that accounted for Enrico Piaggio’s observation of the prototype: ‘Sembra una Vespa’ (It looks like a wasp).

In less gender-equality-minded times, when it was indecorous for a woman to wear trousers, this defining feature of the design, along with the protective fairing at the front, made the Vespa particularly appealing to women (viz Audrey Hepburn’s chaotic attempts to control a runaway Vespa in Roman Holiday)… not to mention to Italian men who did not want to get their snappily tailored suits dirty.

___

This guest blog post is brought to us by Nick Foulkes of Luke Irwin Rugs Ltd.

See the original post here.