Born on September 14th, 1917 in Innsbruck, Austria and died on New Year’s eve 2007 in Milan. His father who shared his name and profession moved to Turin so that his junior could study Architecture at Politecnico di Torino. The elder Ettore was a traditionalist, his son wanted to be everything that he was not, drawn to bold shapes and colours, often bending and breaking the rules of Architecture and Design. After graduation, Ettore was drafted into the Italian military to fight in the Balkan Campaign, was captured and held in a POW camp in Yugoslavia.

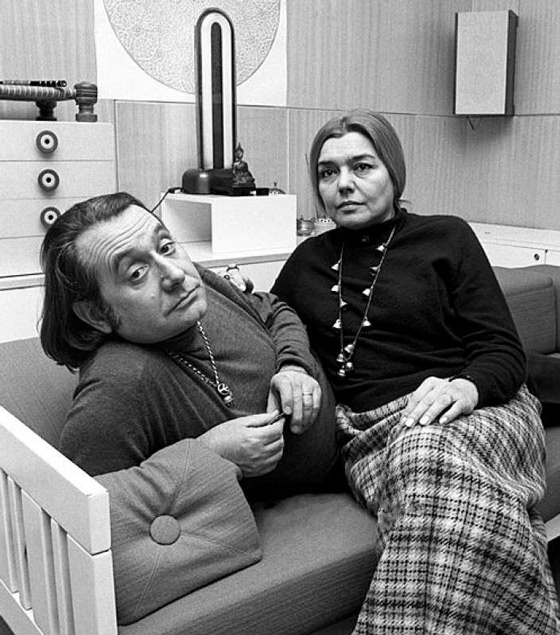

After the war, he married Fernanda Pivano. Pivano was a prolific writer and translator, working closely with Hemmingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Dorothy Parker, William Faulkner, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, Gregory Corso, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Photo taken by Ettore – Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg, Dylan and Peter and Julian Orlofsky

_

They moved to NYC where Sottsass began working for George Nelson. Though his work there only lasted a few months, Nelson made a big impression on Sottssas. Perhaps not so much in colour-ways, material selections or applications but in attitude and demeanour. Here’s an excerpt from George Nelson: The Design of Modern Design where Ettore recalls first meeting Nelson.

_ _

“George Nelson was traveling effortlessly on our wavelength, possibly because he had been in Italy a few years but mainly because his mental mechanisms, his curiosities, and his enthusiasms had no borders; they were not provincial; they roamed everywhere, in all directions, imagining history and “histories” continually expanding in a global sphere. George Nelson’s existential vision acknowledged no compartments, partition walls, specializations, or special keys. Life and thought, the irrational, the rational, the true and the imaginary, were for him open regions, permanent collages, continuous landscapes to be crossed. Anyway, that evening long ago perhaps we became friends, more by words unspoken than spoken, more by hopes announced than by established programmes, more by mysterious necessities or mysterious inclinations than by any sort of certainties. He said to me: “Why don’t you come and see me in New York?” I told him I didn’t have enough money. Italy was in a disastrous state, and so was I. He said: “Come and work with me for a while.” “Really?” I said…. I found myself in New York, a black, opulent city, invaded by yellow cabs, unexpected fumes, and green glass canyons, after a very long flight on a Constellation, probably a war relic. The evening I arrived I went to sleep at George’s place. George had a large, modern, dark apartment, with lamps hidden in the ceiling from which beams of theatrical light descended. Then there was the furniture designed by him, long elegant, subtle pieces, lacquered in gray and orange, with attractive drawers and tiny handles, resting on black carpets, and then plastic Danish, smooth, dark red cups, and tables in stainless steel and white plastic laminate, all polished and sophisticated, all as mysterious as a hidden ritual…”

_ _

He moved back to Italy, full of new impressions and ideas, this is when he seemingly found comfort in the unusual and became more courageous than ever, his definitive style began to take shape. In 1958, Sottsass was hired by Adriano Olivetti as a design consultant for Olivetti, to design electronic devices and develop the first Italian mainframe computer, the Elea 9003 (pictured below) for which he was awarded the Compasso d’Oro in 1959.

He also designed office equipment, typewriters, and furniture. There Sottsass made his name as a designer who, through his unique brand of styling, managed to bring office equipment into the realm of popular culture. His first typewriters, the Tekne 3 and the Praxis 48, were characterized by their sobriety and their angularity. With Perry A. King, Sottsass created the Valentine in 1969 (below) which is considered today as a milestone in 20th century Design.

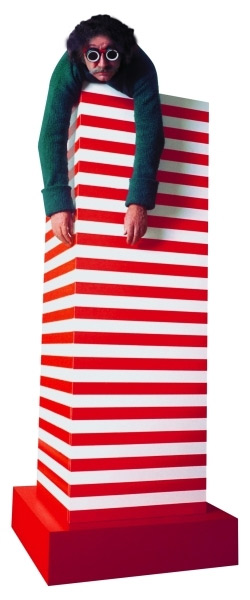

While continuing to design for Olivetti in the 1960s, Sottsass developed a range of objects which were expressions of his personal experiences traveling in the United States and India. These objects included large altar-like ceramic sculptures and his “Superboxes”, radical sculptural gestures presented within a context of consumer product, as conceptual statements. Covered in bold and colorful, simulated custom laminates, they were precursors to Memphis, a movement which came more than a decade later. Around this time, Sottsass said: “I didn’t want to do any more consumerist products, because it was clear that the consumerist attitude was quite dangerous.” As a result, his work from the late 1960s to the 1970s was defined by experimental collaborations with younger designers such as Superstudio and Archizoom Associati, and association with the Radical movement. Sottsass was given a grim prognosis – back then a diagnosis of nephritis, which affects the kidneys, was basically a death sentence. Roberto Olivetti, no doubt indebted to Sottsass for his contributions, funded a groundbreaking treatment program for the designer at Stanford University and saved Sottsass from certain death.

While continuing to design for Olivetti in the 1960s, Sottsass developed a range of objects which were expressions of his personal experiences traveling in the United States and India. These objects included large altar-like ceramic sculptures and his “Superboxes”, radical sculptural gestures presented within a context of consumer product, as conceptual statements. Covered in bold and colorful, simulated custom laminates, they were precursors to Memphis, a movement which came more than a decade later. Around this time, Sottsass said: “I didn’t want to do any more consumerist products, because it was clear that the consumerist attitude was quite dangerous.” As a result, his work from the late 1960s to the 1970s was defined by experimental collaborations with younger designers such as Superstudio and Archizoom Associati, and association with the Radical movement. Sottsass was given a grim prognosis – back then a diagnosis of nephritis, which affects the kidneys, was basically a death sentence. Roberto Olivetti, no doubt indebted to Sottsass for his contributions, funded a groundbreaking treatment program for the designer at Stanford University and saved Sottsass from certain death.

_

_

_

Sottsass and Fernanda Pivano divorced in 1970, and in 1976 Sottsass married Barbara Radice, an art critic and journalist. When Roberto Olivetti took the head of the family company, he named Sottsass artistic director and gave him a high salary, but Sottsass refused. Instead he created the Studio Olivetti independently working Olivetti and became instantly the most creative international centre of design associating research with creation and industrial strategy. The feeling that his creativity would have been stifled by corporate work is documented in his 1973 essay “When I was a Very Small Boy” In 1968, the Royal College of Art in London granted Sottsass an honorary doctoral degree.

_

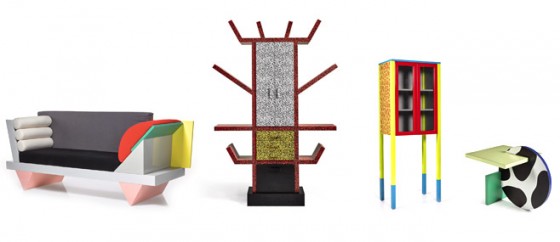

Ettore Sottsass founded the Memphis Group in Milan on December 11, 1980, after the Bob Dylan song “Stuck inside of mobile with the Memphis blues again” played during the group’s inaugural meeting. Industrial design took great strides during the 20th century led by great analytical minds like Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer. They followed logical paths where form always followed function, they were highly rational, often being symmetrical and unadorned, ornate styles virtually disappeared form mass-produced pieces during this era.

Sotsass wanted to explore deeper relationships that develop between person and thing, to prompt unusual and explorative human behaviour, to approach function like a psychologist rather than an scientist in order to expose the potential impact of design language on the human psyche. Memphis pieces give physical forms to abstract ideas and provoke an emotional response instead of a quiet intuitiveness. There seemed to be a constant underlying theme, commenting on social hierarchies ultimately giving the pieces deeper meanings. Luxury materials married with obviously low cost ones, symbolically laughing off the distinctions between socio-economic classes, inventing a new unassuming narrative. This theme is exemplified by their Marble Sofa.

_

_

While function was not king, Memphis pieces, often considered art or decoration and not furniture or functional works, always served their intended purposes. Even if it was not clearly apparent, Memphis reached further than the others finding a higher purpose than just practicality, making them more “practical” in a sense when their work is viewed from alternative perspectives which the Memphis pieces force you to do.

_

Ettore once said that “Memphis is like a very strong drug, you cannot take too much. It’s like eating only cake.” _

Shiva vase for BD Barcelona, Nine-O chair for Emeco, Mandarin for Knoll, Glass Work for Venini

_

The group was dismantled by Sottsass in 1988. Recently, there has been a revival of the group. Seen nowadays as a radical historic group, it served as inspiration for the Fall/Winter 2011-2012 Christian Dior haute couture collection and for the Fall/Winter 2015 Missoni collection.

The group most iconic work is the “Carlton” room divider designed by Sottsass in 1981.

Around the same time as the birth of the Memphis Group, Sottsass founded his own design office, Sottsass Associati which is still in practice creating furniture and buildings with Ettore’s flare. Though primarily an Architectural firm, Sottsass Associati also practices industrial design with leading companies such as Apple, Philips, Siemens, Zanotta, Fiat, and Alessi, occasionally bringing in former members of the Memphis Group on these projects.

The man defied his father, his professors and his colleagues. He refused to follow the sacred rules of Design and Architecture. He was a rebel and we are grateful that he found a way to make the world love him for it.

“Now the bricks lay on Grand Street Where the neon madmen climb They all fall there so perfectly It all seems so well timed”

– Bob Dylan